National Building Museum

Welcome to the second edition of Design Spotlight, a monthly blog post that delves into the design of Washington’s architectural marvels and best kept secrets! Read along for an insider’s look at the conflicts, controversies, and personalities that have shaped our Capital City. This month, we’ll explore the National Building Museum, former home of the Pension Bureau.

In the late 1860s, following the Civil War, more than 300,000 Union veterans and their families were owed a pension. Military pensions made up almost one third of the federal budget at that time, and an army of 1,500 clerks was needed to process all of the paperwork.

In 1881, Montgomery C. Meigs, Quartermaster General of the Union army, was tapped to design a building that could house this massive operation. Known for his boundless energy, blunt personality, and fastidious record keeping, Meigs had already contributed much to the war effort and the development of Washington, DC.

He had managed the Union Army’s supply chain during the war, designed and developed Arlington National Cemetery, engineered the “new” cast iron dome of the US Capitol, and was involved in architecture and engineering projects across the city. At the age of 66, Montgomery Meigs had already spent a long career in service to the country, and many of his contemporaries were hoping he would step down after one last commission.

Meigs envisioned the Pension Office as his final and greatest legacy– a monument to the sacrifice and glory of Civil War soldiers. Meigs wanted to be sure that fellow veterans felt no expense was spared in the full execution of their due benefits. The building was also intended to serve as an event space for Washington’s large social and political functions.

Breaking away from the established Neo-classical aesthetics of Washington at the time, Meigs based the exterior of the Pension Building on the Palazzo Farnese in Rome, Italy, which he had visited years earlier. The Palazzo was built in 1517 for the wealthy Farnese family as a lavish city residence. It was expanded for Pope Paul III, a Farnese, by none other than Michelangelo. Meigs copied the exterior decorative patterns and windows of the Palazzo almost exactly, but added a modern gabled roof and skylights to allow light and fresh air to reach deep into the building.

Breaking away from the established Neo-classical aesthetics of Washington at the time, Meigs based the exterior of the Pension Building on the Palazzo Farnese in Rome, Italy, which he had visited years earlier. The Palazzo was built in 1517 for the wealthy Farnese family as a lavish city residence. It was expanded for Pope Paul III, a Farnese, by none other than Michelangelo. Meigs copied the exterior decorative patterns and windows of the Palazzo almost exactly, but added a modern gabled roof and skylights to allow light and fresh air to reach deep into the building.

Meigs also included a dramatic terracotta frieze that wraps around the exterior walls. This distinctive work was carved by sculptor Caspar Buberl and depicts scenes from the Civil War, including the movement of infantry, navy, artillery, cavalry, and quartermaster units. Meigs, always scrupulous with government funds, directed Buberl to sculpt only 70 feet of unique scenes. Burberl then cast each panel multiple times, adding or subtracting a few figures, to wrap the full 1,200 feet around the building. Meigs also insisted that African American teamsters be prominently included over the West entrance.

Meigs also included a dramatic terracotta frieze that wraps around the exterior walls. This distinctive work was carved by sculptor Caspar Buberl and depicts scenes from the Civil War, including the movement of infantry, navy, artillery, cavalry, and quartermaster units. Meigs, always scrupulous with government funds, directed Buberl to sculpt only 70 feet of unique scenes. Burberl then cast each panel multiple times, adding or subtracting a few figures, to wrap the full 1,200 feet around the building. Meigs also insisted that African American teamsters be prominently included over the West entrance.

The Great Hall in the center of the building spans 316 feet of open space, with offices wrapped around the periphery. Massive 90 foot Corinthian columns, each constructed from 55,000 bricks and painted to look like marble, support the steel roof. Meigs opted for brick because it was fireproof and less expensive than stone. The entire Pension Building is made from more than 15 million bricks, making it one of the largest brick buildings in the world. Workmen and those close to Meigs joked that he had probably counted every single brick.

The Great Hall in the center of the building spans 316 feet of open space, with offices wrapped around the periphery. Massive 90 foot Corinthian columns, each constructed from 55,000 bricks and painted to look like marble, support the steel roof. Meigs opted for brick because it was fireproof and less expensive than stone. The entire Pension Building is made from more than 15 million bricks, making it one of the largest brick buildings in the world. Workmen and those close to Meigs joked that he had probably counted every single brick.

Underpinning the grandness of Meigs’ design was a remarkable and thoughtful functionality. Unlike the traditional cramped office conditions of the nineteenth century, Meigs aimed to create a healthy and pleasant work environment for the Pension staff. He designed an ingenious ventilation system to keep air circulating and maximize natural light. He specified that stairs between floors should be wide and shallow to accommodate veterans on crutches. On the fourth floor balcony, Meigs installed a “document trolley” and dumbwaiters to move buckets full of papers around the building with minimal effort. Finishing touches included planters with double eagle heads to line the railing of the third floor balcony. The planters in the building today are recreations—all of the originals disappeared by the 1920s, but one was found in the front yard of a Washington home, and replicated.

Underpinning the grandness of Meigs’ design was a remarkable and thoughtful functionality. Unlike the traditional cramped office conditions of the nineteenth century, Meigs aimed to create a healthy and pleasant work environment for the Pension staff. He designed an ingenious ventilation system to keep air circulating and maximize natural light. He specified that stairs between floors should be wide and shallow to accommodate veterans on crutches. On the fourth floor balcony, Meigs installed a “document trolley” and dumbwaiters to move buckets full of papers around the building with minimal effort. Finishing touches included planters with double eagle heads to line the railing of the third floor balcony. The planters in the building today are recreations—all of the originals disappeared by the 1920s, but one was found in the front yard of a Washington home, and replicated.

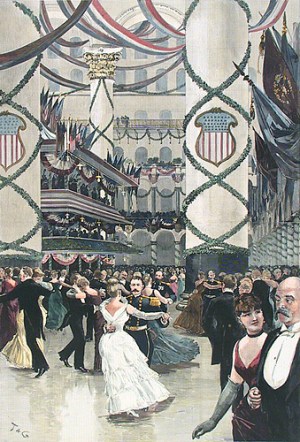

Not everyone approved of Meigs’ design for the Pension Building; some of his critics considered it a blaring eyesore, calling it the “Old Big Red Barn.” Fellow Civil War general Philip Sheridan quipped, “Too bad the damn thing is fireproof.” But the Pension Building soon became a sought-after venue for Washington events. Five inaugural balls were held in the Great Hall in the first twenty years of completion—Grover Cleveland, Benjamin Harrison, William McKinley, Teddy Roosevelt, and William Howard Taft. Cleveland was so eager to take advantage of the new hall that workers erected a temporary roof for his inauguration before construction was even complete. Contemporary presidents have also hosted events in the Pension Building, including Richard Nixon, Jimmy Carter, Bill Clinton and Barack Obama.

Over the last 130 years, many tenants have been housed in the former Pension Office. The Pension Bureau moved out in 1921 after a reorganization following WWI. The building was occupied by various government agencies until the 1960s, when it has fallen into bad repair. Briefly considered for demolition, the building was saved by conservationists and added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1969. In 1980 it was earmarked for a future museum, and the National Building Museum opened its doors in 1985.

Today, the museum showcases the impact, history, and stories of the built environment. Thousands of visitors pass through the Great Hall every day. The National Building Museum also runs special programming for adults and children, including the popular Summer Block Party series of interactive temporary structures in the Great Hall. This year the museum has partnered with design firm Snarkitecture to create Fun House, a re-imagining of the traditional suburban home, complete with warped furniture, half-constructed walls, pillow forts, and a giant ball-pit pool.

From paper pushing to playground, the Pension Office turned National Building Museum has reinvented itself over the past 130 years to become a hidden gem among Washington’s vast museum offerings.

Learn more about the National Building Museum at www.nbm.org. The museum is open 10am-5pm, and conveniently located across from the Judiciary Square Metro station at 401 Fst NW.

#architecture #CivilWar #MontgomeryMeigs #WashingtonDC #nationalbuildingmuseum