Legacy of the Smithsonian

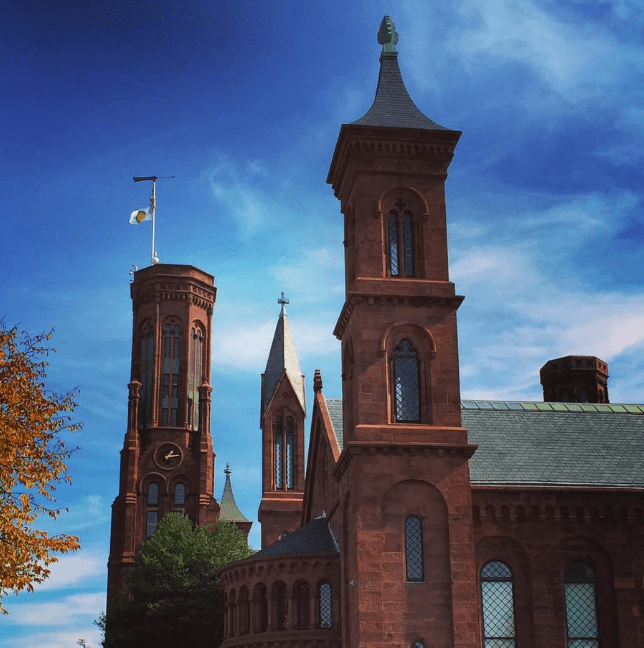

![legacy 6 a large brick building with a clock tower]()

Welcome to the third edition of Design Spotlight, our blog series that delves into the design of Washington’s architectural marvels and best-kept secrets! Here you can learn about the conflicts, controversies, and personalities that have shaped our capital city—then take a tour to see the sites and hear the stories for yourself! In this edition, we’ll explore the origin of the Smithsonian Institution, our “Nation’s Attic” along the National Mall.

The eastern side of the National Mall, between the Washington Monument and the Capitol Building, is surrounded by the Smithsonian Institution, one of the largest museum complexes in the world. There are 19 museums along a mile stretch of the Mall, which house over 150 million items in the collection. Five other museums are located in the surrounding DC area, plus two more in New York City. The Smithsonian Institution, which receives over 30 million visitors a year, is lovingly referred to as the “Nation’s Attic.”

The eastern side of the National Mall, between the Washington Monument and the Capitol Building, is surrounded by the Smithsonian Institution, one of the largest museum complexes in the world. There are 19 museums along a mile stretch of the Mall, which house over 150 million items in the collection. Five other museums are located in the surrounding DC area, plus two more in New York City. The Smithsonian Institution, which receives over 30 million visitors a year, is lovingly referred to as the “Nation’s Attic.”

The Institution is named for James Smithson, a wealthy British scientist who donated his wealth and life’s work to the United States. Smithson, born in 1765, was an illegitimate son of Hugh Percy, the First Duke of Northumberland, and Elizabeth Macie. Macie was secreted away to Paris where Smithson was born out of wedlock, and thus never inherited his father’s title or wealth. But with financial backing from his mother’s large estate, Smithson pursued a career in science. He graduated from Pembroke College, Oxford in 1782, and then traveled extensively throughout Europe.

The Institution is named for James Smithson, a wealthy British scientist who donated his wealth and life’s work to the United States. Smithson, born in 1765, was an illegitimate son of Hugh Percy, the First Duke of Northumberland, and Elizabeth Macie. Macie was secreted away to Paris where Smithson was born out of wedlock, and thus never inherited his father’s title or wealth. But with financial backing from his mother’s large estate, Smithson pursued a career in science. He graduated from Pembroke College, Oxford in 1782, and then traveled extensively throughout Europe.

Smithson’s wealth allowed him to pursue a wide variety of scientific study. He was involved in research from botany, to geology, to chemistry. He even discovered a new element, now on the periodic table as “Smithsonite.”

Smithson came of age in a time of intense scientific discovery and political upheaval. He had little loyalty to his native France—he was taken prisoner by both sides during the Napoleonic Wars. And he didn’t much care for England either—he resented his bastard status and regarded the British monarchy as a “most contemptible encumbrance.” Though he wrote little on politics, Smithson was disenchanted with Europe, and perhaps interested in the concept of democratic government and the newly born United States.

Smithson’s research eventually brought him to Genoa, Italy, where he died in 1829 at the age of 64. Having never married or fathered children, Smithson left his estate to his nephew, Henry James Hungerford, on the condition that Hungerford have children of his own to inherit it. If Hungerford had no children, Smithson wrote in his will, “I then bequeath the whole of my property. . . to the United States of America, to found at Washington, under the name of the Smithsonian Institution, an Establishment for the increase & diffusion of knowledge among men”.

It is not known why Smithson made this generous decision, as he never expressed written interest in funding a scientific organization in the United States, and generally wrote little on his own opinions. Contemporary historians are left to speculate as to his motivations. Smithson was clearly dedicated to making his scientific mark on the world, and perhaps considered the United States as the best place to fulfill that life long goal.

Hungerford died childless in 1835. U.S. President Andrew Jackson, still suspicious of the British after the War of 1812, received word from an American diplomat in England about Smithson’s generous donation. Congress dispatched John Quincy Adams, former President and then Congressman, to retrieve Smithson’s estate. As Congress debated on the future of the donation, John Quincy Adams championed the fulfillment of Smithson’s will and establishment of the Institution. Adams and former U.S. Attorney General Richard Rush undertook three long years of negotiation with the British government. Finally, in 1858, Smithson’s donation arrived— eleven boxes of gold coins worth about $500,000 ($11 million today), as well as Smithson’s life’s work. His scientific notes, mineral collection, and library were also bequeathed to Congress. Unfortunately most of those artifacts were destroyed in a fire at the Smithsonian Castle in 1865.

Hungerford died childless in 1835. U.S. President Andrew Jackson, still suspicious of the British after the War of 1812, received word from an American diplomat in England about Smithson’s generous donation. Congress dispatched John Quincy Adams, former President and then Congressman, to retrieve Smithson’s estate. As Congress debated on the future of the donation, John Quincy Adams championed the fulfillment of Smithson’s will and establishment of the Institution. Adams and former U.S. Attorney General Richard Rush undertook three long years of negotiation with the British government. Finally, in 1858, Smithson’s donation arrived— eleven boxes of gold coins worth about $500,000 ($11 million today), as well as Smithson’s life’s work. His scientific notes, mineral collection, and library were also bequeathed to Congress. Unfortunately most of those artifacts were destroyed in a fire at the Smithsonian Castle in 1865.

While Smithson bequeathed his entire estate to the United States, he (or at least his body) didn’t travel to America until over 70 years after his death. When Smithson died in 1829, he was buried in a Protestant cemetery in Genoa, Italy. But in 1903, the town sought to redevelop the land. City leaders invited the Smithsonian Institution to come collect their patron. Alexander Graham Bell, then regent of the Institution, traveled to Genoa with his wife to exhume and transport Smithson to Washington, D.C. During the month-long journey, the Smithsonian Institution’s board appealed to Congress to fund a final resting place for their benefactor. Although prominent architects from around the world submitted impressive designs for the tomb, Congress declined to fund the project.

Instead, the Institution re-purposed a janitor’s closet in the museum headquarters, and put Smithson’s remains in a pared-down version of a sarcophagus designed by sculptor Gutzon Borglum, of Mt. Rushmore fame. The renovated closet with its modest sarcophagus was meant to be a temporary solution until Congress approved funds for something grander, but Smithson remains there to this day.

Our next Design Spotlight will focus on the Smithsonian Institution’s original home, and the final resting place of James Smithson: the Smithsonian Castle.

Learn more about the fate of James Smithson and design of the Smithsonian Museums on our Museums of the National Mall Tour, and check back for more Design Spotlights!

#smithsonian #museums #architecture #walkingtours #WashingtonDC

The eastern side of the National Mall, between the Washington Monument and the Capitol Building, is surrounded by the Smithsonian Institution, one of the largest museum complexes in the world. There are 19 museums along a mile stretch of the Mall, which house over 150 million items in the collection. Five other museums are located in the surrounding DC area, plus two more in New York City. The Smithsonian Institution, which receives over 30 million visitors a year, is lovingly referred to as the “Nation’s Attic.”

The eastern side of the National Mall, between the Washington Monument and the Capitol Building, is surrounded by the Smithsonian Institution, one of the largest museum complexes in the world. There are 19 museums along a mile stretch of the Mall, which house over 150 million items in the collection. Five other museums are located in the surrounding DC area, plus two more in New York City. The Smithsonian Institution, which receives over 30 million visitors a year, is lovingly referred to as the “Nation’s Attic.” The Institution is named for James Smithson, a wealthy British scientist who donated his wealth and life’s work to the United States. Smithson, born in 1765, was an illegitimate son of Hugh Percy, the First Duke of Northumberland, and Elizabeth Macie. Macie was secreted away to Paris where Smithson was born out of wedlock, and thus never inherited his father’s title or wealth. But with financial backing from his mother’s large estate, Smithson pursued a career in science. He graduated from Pembroke College, Oxford in 1782, and then traveled extensively throughout Europe.

The Institution is named for James Smithson, a wealthy British scientist who donated his wealth and life’s work to the United States. Smithson, born in 1765, was an illegitimate son of Hugh Percy, the First Duke of Northumberland, and Elizabeth Macie. Macie was secreted away to Paris where Smithson was born out of wedlock, and thus never inherited his father’s title or wealth. But with financial backing from his mother’s large estate, Smithson pursued a career in science. He graduated from Pembroke College, Oxford in 1782, and then traveled extensively throughout Europe.

Hungerford died childless in 1835. U.S. President Andrew Jackson, still suspicious of the British after the War of 1812, received word from an American diplomat in England about Smithson’s generous donation. Congress dispatched John Quincy Adams, former President and then Congressman, to retrieve Smithson’s estate. As Congress debated on the future of the donation, John Quincy Adams championed the fulfillment of Smithson’s will and establishment of the Institution. Adams and former U.S. Attorney General Richard Rush undertook three long years of negotiation with the British government. Finally, in 1858, Smithson’s donation arrived— eleven boxes of gold coins worth about $500,000 ($11 million today), as well as Smithson’s life’s work. His scientific notes, mineral collection, and library were also bequeathed to Congress. Unfortunately most of those artifacts were destroyed in a fire at the Smithsonian Castle in 1865.

Hungerford died childless in 1835. U.S. President Andrew Jackson, still suspicious of the British after the War of 1812, received word from an American diplomat in England about Smithson’s generous donation. Congress dispatched John Quincy Adams, former President and then Congressman, to retrieve Smithson’s estate. As Congress debated on the future of the donation, John Quincy Adams championed the fulfillment of Smithson’s will and establishment of the Institution. Adams and former U.S. Attorney General Richard Rush undertook three long years of negotiation with the British government. Finally, in 1858, Smithson’s donation arrived— eleven boxes of gold coins worth about $500,000 ($11 million today), as well as Smithson’s life’s work. His scientific notes, mineral collection, and library were also bequeathed to Congress. Unfortunately most of those artifacts were destroyed in a fire at the Smithsonian Castle in 1865.